Neither News Nor Fall Song?

On 5th November 2020, Dave Haslam retweeted Martin Hughes-Games:

https://twitter.com/Mr_Dave_Haslam/status/1324280943041982464

@NewsOrFallSong is a Twitter account dedicated to news stories that are supposedly reminiscent of Fall song titles or lyrics. This kind of thing usually leaves me cold, since most Fall songs are not remotely like most of the examples posted. But I'm a miserable pedant, so nobody cares what I think.

Apparently I am supposed to allow others their harmless fun, which I guess I am prepared to do, so long as I am in return allowed my own harmless fun, which mainly involves being unreasonably detailed about what is essentially trivia. Hold on tight!

The posted news story is a startling and peculiar one. Here's the image of the article posted by Martin Hughes-Games:

|

| "Duck Eats Yeast, Quacks, Explodes; Man Loses Eye" |

Basically, the story goes that a prize duck by the name of Rhadamanthus ate some yeast. The duck's owner, one Silas Perkins, discovered the duck in a lethargic ("logy") state, and went to pick it up, at which point the duck quacked and blew up. A "fragment of flying duck" blinded Perkins in one eye.

An unfortunate and astonishing story, if true. The obvious question, of course, is, "is that for real?" So I looked it up in newspapers.com, and found the story easily. It appeared on the front page of the Indianapolis Star, 3 January 1910:

So yes, the story is "real" in that it is true that it really appeared in a newspaper in 1910. But of course that doesn't necessarily make the story true.

Variations of the report are to be found in many contemporary newspapers and other publications and have been posted to the internet for amusement from time to time. It's not easy to work out whether people are discovering the story independently, or if it all goes back to an original posting somewhere.

On 3 January 2013, R.L. Ripples (@TweetsofOld) Tweeted a newspaper clipping of the story from a different source. That's the earliest appearance on the internet I have found so far. The same Twitter account retweeted the story for several years running from 2013: 2014, 2015, 2017, 2019.

A Smokstak Antique Engine Community forum post on 26 April 2014 seems to have been a serendipitous and independent find, in a journal called The Locomotive. According to that publication, the story was forwarded to them as a clipping from the St. Louis Post-Despatch of 4 January 1910, with a (presumably humorous) request for advice on the size of safety valve a duck should have.

My next visit was to snopes.com. They published a piece about the meme on 10 May 2020, written by Snopes founder David Mikkelson.

Mikkelson comments that "[t]his account did in fact run in dozens of newspapers across the U.S. in January 1910, with slight variations in dating and wording." But he concludes that,

our attempts to track down any additional information about the plight of Rhadamanthus and Silas Perkins more than a century after the fact have not proved fruitful. We can say, however, that this account appears to fall into the category of extremely implausible tall tales...

Mikkelson goes on to discuss the avian digestive/intestinal system and decides that the story is biologically unlikely. The issue of the origin of the newspaper reports is pursued no further by Snopes.

But the original story, and the question of who wrote it and why, interested me. I thought I could do better than Snopes, so I returned to newspapers.com to see if I could follow the trail any further.

Versions of the story, with just minor differences between them, did indeed appear in dozens of articles mainly between January-May 1910 (most of them in January through March). An outlier is the Clarksville Leaf-Chronicle (Tennessee), dated 6 September 1913.

It might be possible to trace the lineage of the variations of the story, examining its evolution from newspaper to newspaper by tracing key differences in particular phrases. But that's a time-consuming job that I will have to set aside for now.

- Chicago Tribune, 10 February 1965 (story attributed to the Lebanon, Indiana, Patriot of 6 January 1910) [newspapers.com clipping]

- Des Moines Tribune, 17 February 1965 (obviously picking up on the Chicago Tribune piece) [newspapers.com clipping]

The story seems to have been appropriated for advertising purposes in the Chandler News-Publicist (Oklahoma), 28 April 1911. Headlined, "The Story of Silas And His Duck Rhadamanthus", the item concludes, "Silas had one of Fred B. Hoyt's accident policies and received $2,-500 for the loss of his eye. Every wise man ought to have one of those policies." [newspapers.com clipping]

I wondered if the exploding duck story had been seeded solely for the benefit of Fred B. Hoyt, but when I couldn't find any other similar adverts I decided Hoyt had probably been opportunistic rather than strategic. But the existence of the advert, a year after the original appearance of the exploding duck story, does perhaps suggest that the story was well known and remembered even then.

Rhadamanthus the exploding duck pre-1910

Further research revealed that 1910 was not the first time Rhadamanthus had exploded in print. The story actually has its origins in a syndicated column that had appeared in 1909.

Here's one of the earlier versions of the duck story. It looks like it was originally based in NJ. If you search for that town ("Cedar Grove N.J.") in papers from about 1909-1913, there's no end to the bizarre animal stories, though most seem dubious.

Welcome to Cedar Grove

What is now Cedar Grove was originally incorporated by an act of the New Jersey Legislature as the Township of Verona on February 7, 1892, from portions of Caldwell Township. Portions of the township were taken to create Verona borough, based on the results of a referendum held on April 30, 1907. On April 9, 1908, the name was formally changed to Cedar Grove.

- A Remarkable Invention: "STEPOMETER" gives advance information and is always a winner. 27 June 1909 (miscellany section, (p.3). * [newspapers.com clipping]

- Two Remarkable Roosters: story of the Damon and and Pythias of the Jersey poultry world. 15 August 1909 (miscellany section, p.2). * [newspapers.com clipping]

- Biggest Cold Storage Egg: It hatched out an ostrich when placed in an igloo incubator. 23 January 1910 (miscellany section, p.4). [newspapers.com clipping]

- A Savage Ground Hog: Whipped two bloodhounds and was too busy to see his shadow, 13 February 1910 (miscellany section, p.2). * [newspapers.com clipping]

- A Most Wonderful Cow: This remarkable bossie feasts on gasoline and her milk can run an auto, 13 February 1910 (miscellany section, p.3). * [newspapers.com clipping]

- Dog Dislikes "Lohengrin": Jersey squire stops St. Bernard's howls with a phonograph. 23 April 1910 (p.6). [newspapers.com clipping]

- Time-Telling Cat Dead: Tail pointed to to run-down clock as end came. 23 August 1910 (p.6). [newspapers.com clipping]

- Dog Knows Name in Print. 14 October 1910 (p.6). [newspapers.com clipping]

- With the Nature Fakers: Testing tuneful cats to save waste in making violin strings. 10 October 1911 (p.6). [newspapers.com clipping]

- With the Nature Fakers: Rooster dies of old age same day he is hatched! 9 June 1912 (p.4). * [newspapers.com clipping]

- Tried to Bunko Nature. 16 June 1912 (miscellany section, p.3). * [newspapers.com clipping]

|

| Thomas Edison Gets Some Posers from Si Perkins: Cedar Grove Board of Poultry Trade Tests Wizard's Practical Knowledge. By Farmer Smith [newspapers.com clipping]. |

Who Was George Henry Smith (AKA Farmer Smith)?

"... if you have a lot of trouble in this world, you will have a fair show of making a good writer for children, for the sympathy and tenderness which has been beaten into you will show in the stories and charm the little ones." - Farmer Smith, 1914,

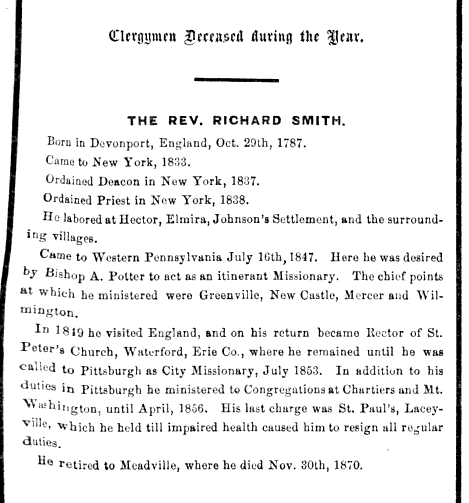

So it seems the Smith family emigrated to New York in 1833, where Richard entered the priesthood. Richard Salt also became a clergyman. Amelia married one. George Henry took a different path.

I quoted above Farmer Smith's comment that a children's writer would benefit in some way from having experienced "a lot of trouble in this world." The death of Farmer Smith's father is perhaps the first tragedy from his own life that he may have had in mind. The details can be found in contemporary newspaper reports (see newspapers.com clipping for the account in the Knoxville Daily Tribune of 21 December 1876).

At about 2:30am on the morning of 20th December 1876, a nightwatchman at Burr & Terry's lumber yard noticed a fire at a warehouse owned by Allison & McClung. He sounded the alarm, and the fire-warning bell at city hall was rung. By the time fire-fighters arrived, and despite their best efforts, the fire was out of control and the building and its contents were lost. In front of the warehouse was a track, upon which were several railway cars. Most of these were removed, except one which was loaded with coal. A group of men came forward to roll it away, including George Henry Snr who pushed from the side nearest the warehouse. Suddenly, the warehouse walls, weakened by the fire, collapsed "with a crash like muffled thunder, burying Mr. Smith beneath the crushing weight." George Henry was the only person killed. He could only be identified by the papers in his pockets.

A more detailed account of the fire can be found here (Knoxville's Million Dollar Fire blog), including a map of the buildings involved :

The incident is also covered here (City of Knoxville, History of Fire Department), albeit incorrectly dated.

Friday evening at 6 o'clock, Chas. E, Ryan, a city salesman for Anderson Dulaney, Varnell company, was returning from a trip in his buggy in the upper end of Knox county. At the Boyd's ferry bridge he saw a crowd of men who had found Smith under the bridge, about half clad. Getting out of his buggy, and knowing of Smith's disappearance, Mr. Ryan asked Mr. Smith to ride with him. Mr. Smith at once accepted the invitation and got in the buggy with Mr. Ryan. One of the citizens of that section then notified the sheriff's office by telephone of the finding of Mr. Smith.

Mr. Ryan states that as they drove along Mr. Smith told him he wanted to go to a Roman Catholic priest as he wished to make a confession. Mr. Ryan agreed to go with him to a priest and they came toward the city, Ryan hoping to meet an officer.

When they reached the forks of the roads, Ryan wanted to go the road the sheriff was coming. When Smith, who knew nothing about the sheriff's coming, said, "something tells me I must go this way." They drove down the direction he indicated when they came to a dense woodland. Smith said "Whoa," and the horses stopped. Smith jumped from the buggy and disappeared in the woods. Mr. Ryan, who was unable to stop him, went back to the forks of the road, where he met a deputy sheriff and notified him of Smith's escape, and came on to the city.

Source: Knoxville Sentinel, 15 August 1908, p.1 [newspapers.com clipping], p.2 [newspapers.com clipping]. See also the account in the Knoxville Journal and Tribune, 16 August 1908, p.5 [newspapers.com clipping].

Worldcat, an international union catalogue of thousands of libraries, contains just two of Smith's books: one record for Daddy's Good Night Stories (Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library, New York), and one for The Dollie Stories (Richmond Public Library, Virginia). The Library of Congress has got a copy of Daddy's Good Night Stories, but apparently nothing else.

Smith had his own company, Farmer Smith Incorporated (founded in 1912), described as doing "nearly everything under the sun in the printing and publishing line".

Like the children's story books, surviving titles published by Farmer Smith Incorporated are few and far between. Only On Picture-Play Writing: a handbook of workmanship by James Slevin (1912) seems to have had some longevity. There was also a magazine called Farmer Smith's Magazine, but I've not been able to locate any copies.

Smith does also seem to have been a poultry breeder.

The magazine Poultry Success, dated February 1906 carries a letter from him (p.85) giving advice in reply to a "J.H. of Chicago" who had written complaining that his wife didn't like poultry. And the issue dated December 1906 contains the following item (p.38):

George Henry Smith, a New York business man of Cedar Grove, N.J., obtained 2,229 eggs in 12 months from an average of 18 hens on a city lot. The breeds were Barred Rocks and S.C. Buff Leghorns.

A few years' later, Smith wrote about his career in Printers' Ink, the magazine for the advertising industry (see sources for full citation):

I've always thought I ought to tell you how I came to be an advertising man, and how PRINTERS' INK helped.

I decided to go to Yale, and being uncertain as to my future career, I asked a well-known man what he thought would be the best profession. His advice was to go to college and by that time a new profession would bob up.

Soon after that I went into the Y.M.C.A. rooms, Knoxville, Tenn., and picked up a copy of PRINTERS' INK. I had not read very far when the thought struck me, this for me.

I noticed in there that PRINTERS' INK was advertising to give a year's subscription to any young man anywhere who would send in an interview with a local merchant regarding what the said merchant had found profitable in advertising. This was for me again.

I put on my hat, went out, secured the interview and a subscription to PRINTERS' INK for a year.

Upon arriving at Yale I got my laundry done by writing ads. I did column after column of work for the local merchants, most of which was set up in my own printing office and placed directly by me.

During all this time I was not only a close reader, but also a contributor to PRINTERS' INK, and later on, when I established my own business, I used it very effectively, and the training that I got from reading the Little Schoolmaster was not only of value to me as an advertisement writer, but also upon the work that I was to undertake later upon the New York Times. So, you see, I owe a lot to PRINTERS' INK.

Printers' Ink also published an interesting piece about Smith which contextualises his writings. Recall that "Cedar Grove" was a new name for a small town when Smith began writing about it. The Cedar Grove articles can be seen, therefore, as a form of advertising for the town. The piece appeared in the "Flips and Flings from a Cynic" column in 1909 (Vol. 68, pp.26-27):

Ever heard of Cedar Grove, N.J?

Well, it's the home of George Henry Smith and the Sile Perkinses and Granddaddy Hank, etc., etc.

When George Smith was on the New York Times, hustling out after boarding-house ads, nobody thought he was a great many pumpkins. Nobody even suspected that he had a Henry to use as a ham to sandwich his name.

It all began when George moved out to Cedar Grove - which has just 500 inhabitants if you count the station cat and all the dogs. George got exceedingly tired of having people saying, when they heard where he lived, "Cedar Grove - Cedar Grove, where on earth is that?" He sweared a hefty swear that the name of Cedar Grove should yet become a byword on the lips of prattling children.

The first thing that happened was a fascinating telegraph dispatch, dated Cedar Grove, N.J., of half a column in several leading New York dailies, telling how an Erie Railway commuting engine had danced a houchee-couchee on the Cedar Grove siding, to the wonder and terror of the oldest inhabitants. The very next day a similarly dated dispatch told how Farmer Merkle's prize Plymouth hen had committed suicide with a piece of string on a weeping willow tree, because her lord and master had gone off on a trip to the oyster shell dump with another affinity.

The wires kept hot from Cedar Grove, telling one day in the Press about Cynthia, the hen who had amazed the countryside by laying two legs in one day; and the next day in the World how Grandpa Hank, one of the Sile Perkinses, almost swallowed his false teeth when the beagle pub he had buried the day before because a brewery wagon had smashed him, came back as good as new. The New York Sun wrote an editorial about that remarkable hen, Cynthia. The New York papers can't get enough from Cedar Grove, and George Henry is happy. Brave is the man who dares say now, "Where is Cedar Grove?"

Being a truthful man, George Henry Smith gives all the honors to PRINTERS' INK. "If I had never seen P.I., I should not be in the advertising business to-day. How able an advertising man the reading of PRINTERS' INK all these years has made me you may judge when you observe that I have gotten $10,000 worth of advertising for Cedar Grove, not only free, but have been paid for it, besides."

In 1914, "Farmer Smith" (i.e. George Henry Smith) wrote a short piece for The Editor about writing for children, which is generally slight but includes a few hints at something deeper (see sources below for citation):

It is the easiest thing in the world to write a child's story - when you know how. So many people ask me how I do it that I must relieve my mind,

My friend of memory, the late Napoleon, said that imagination rules the world, while I say, "Imagination is the clown of the brain."

To write children's stories, you must live in the child world and that is a hard task. In the first place, children must like you, not you like them. If you are sure the little ones are fond of you, then you have a basis upon which to start writing for little folks.

The words how? and why? are very big in the writer's mind who appeals to youngsters. The man in the moon comes down to earth. How does he get there?

Children love motion and such words as "bumped," "wriggled" and the like. Also queer proper names, like "Old Lady Fiddlesticks" and "Professor Waddlepop."

To the little ones all things are real and the dolls as well as the animals have life and can talk, but in writing anything for children, omit anything negative, also "naughty" and "bad" as far as possible. Try your stories on some child first, for they are terrible critics.

Oh yes, I forgot to say that if you have a lot of trouble in this world, you will have a fair show of making a good writer for children, for the sympathy and tenderness which has been beaten into you will show in the stories and charm the little ones.

It is very hard work to write for youngsters, for it tires the brain so - that is why there are so few children's writers.

But it pays for it gives pleasure to an appreciative audience, who will never forget you, even when you tumble into bed for the last time.

That last paragraph could perhaps serve as an obituary for Smith.

Heart failure killed Farmer Smith on 9th January 1931. He was was buried in Grove Street Cemetery, New Haven.

Largely forgotten now, Smith was perhaps best known and most significant in his day for his work for and with children. But as we've seen, Smith was also identified with the "nature fakes" trend (see Wikipedia), although his work strikes me as "nature whimsy" rather than nature fakery as such.

Assuming Smith followed his own advice, it seems safe to conclude that his "nature fakes" stories of exploding ducks and other adventures in Cedar Grove were not written for children, and they are not specifically mentioned in his Dictionary of American Biography entry. But apparently Smith was writing for children and adults simultaneously. In the early years his pieces appeared anonymously, but I found that by the early 1920s, he used the "Farmer Smith" byline for items about Cedar Grove as well as for his writing for children.

In his piece for The Editor, Smith comments that "if you have a lot of trouble in this world, you will have a fair show of making a good writer for children." It turns out that Smith experienced his share of "trouble in this world", not only losing his father at such a young age (as noted by the Dictionary of American Biography, see below), but also experiencing the early death of a child, and suffering at least one episode of poor mental health.

George Henry "Farmer" Smith died tragically young (he was just 57), leaving behind a written legacy which has become detached from its author and circulated on social media without credit. I'm glad that I've been able to restore his name to his work and document something of his life.

Sources

Farmer Smith (1914). "The Child's Story", in The Editor: the journal of information for literary workers, Vol. 39 (4), 28 March 1914, pp.153-154. Accessed in Hathi Trust Digital Library [Link]

"G.H. Smith, Author for Children, Dies", in New York Times, 10 January 1931, p.11.

"Smith, George Henry" (1935). pp.268-269, In Malone, Dumas (ed.), Dictionary of American Biography (vol. 17). American Council of Learned Societies. Biographical entry written by "V.L.S." (Verne Lockwood Samson). Accessed in the Internet Archive [Link].

Smith, George Henry (1909). "What Decided Him." in Printers' Ink, 20 January, Vol. 66 (3), (p.86). Accessed in Hathi Trust Digital Library [Link].